Originally posted on IPKat.

Reproducibility is an inherent challenge in advanced therapies. Therapeutic extracellular vesicles (EVs), the subject of the recent Board of Appeal case in T 0827/23, are particularly heterogeneous and hard to define products. Aside from the manufacturing and regulatory issues, the inherent heterogeneity of these products also presents a challenge for patentability in Europe. In the biotech field, the EPO will often require data demonstrating the superiority of the invention over the prior art. Patentees must therefore not only demonstrate that their invention works, but also that their invention works better than the prior art technologies. However, the prior art may be even more difficult to reproduce, test and define than the invention itself.

What are extracellular vesicles?

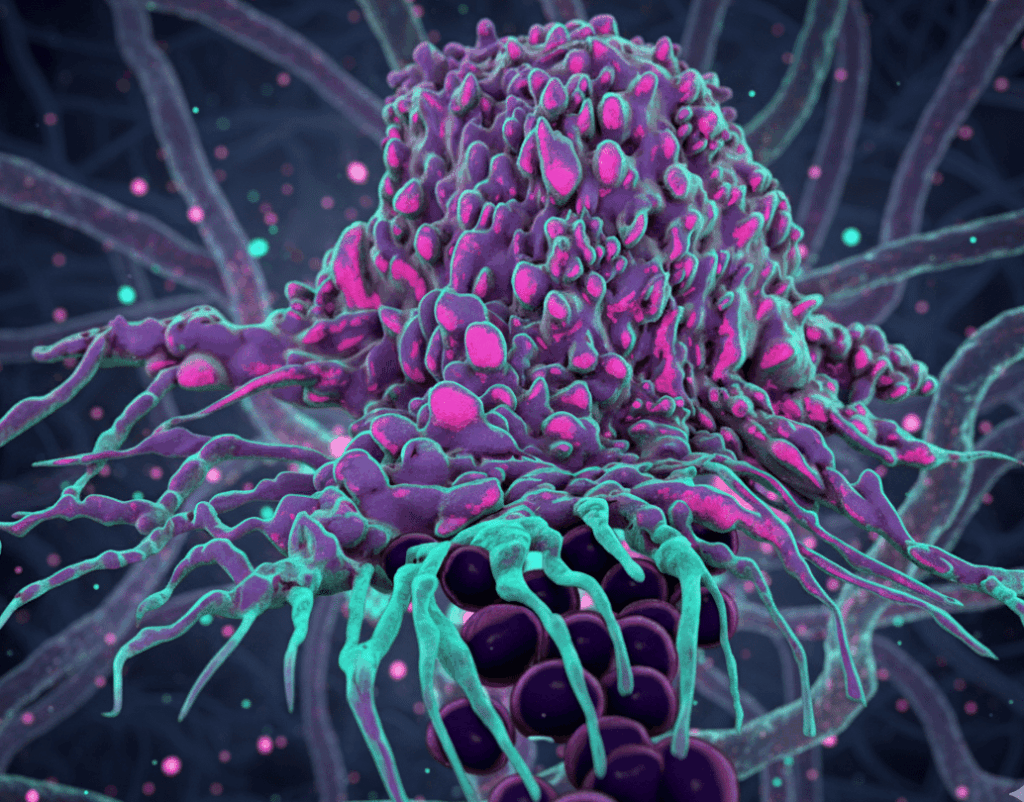

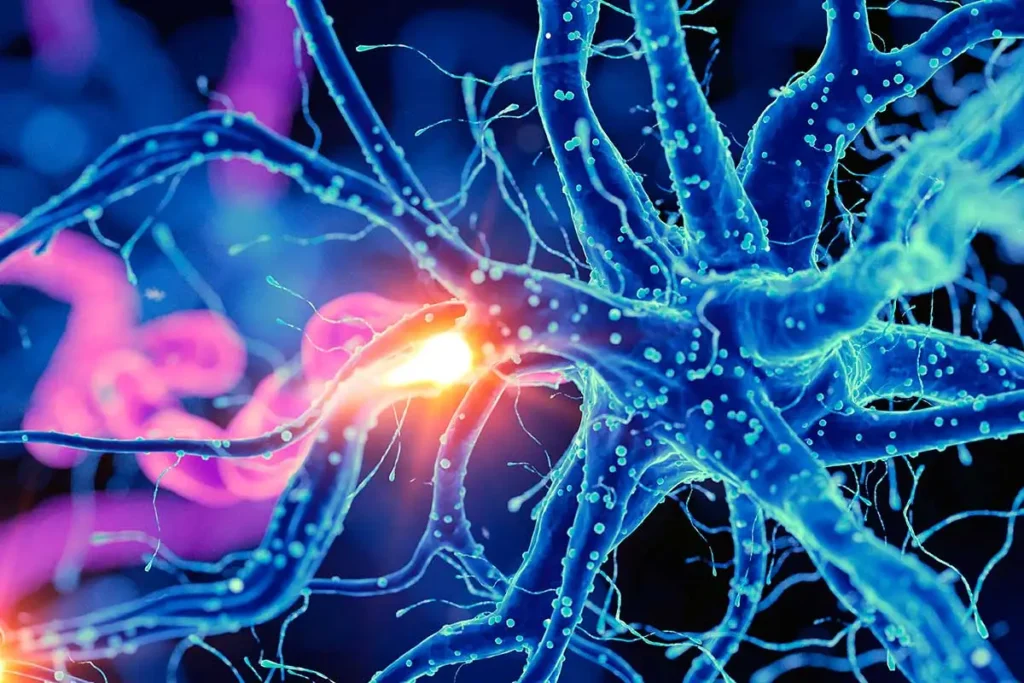

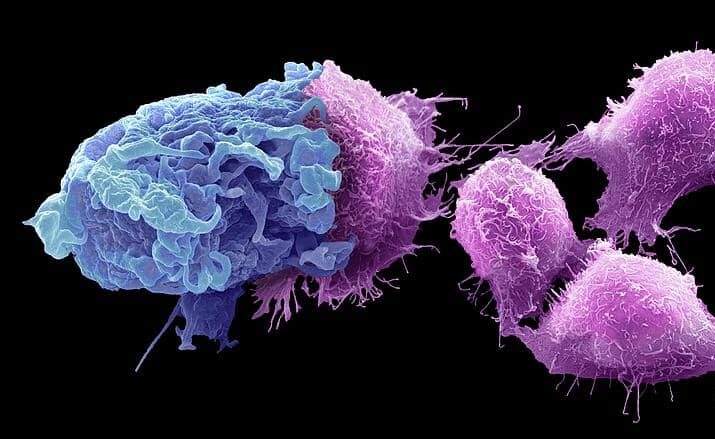

Drugs based on extracellular vesicles (EV) are derived from naturally occurring tiny, membrane-bound particles released by cells. Initially considered mere cellular debris, the physiological functions of EVs are not fully known. However, there is emerging evidence that they play an important role in cell-to-cell communication, transporting a variety of molecules between cells. In terms of pharmaceuticals, extracellular vesicles may either be used as the delivery vehicles or pharmaceutical agents in their own right.

Whilst extracellular vesicles are not cell therapies as such, they have similar characteristics in that they are structurally complex, highly variable and difficult to define. Extracellular vesicles released by cells vary greatly in size and the cellular derived cargo they carry. This natural inconsistency means that even populations of EVs produced from the same cell type are highly heterogeneous. There is also a huge range in the size of EVs. However, even the largest are too small to isolate for individual study.

Examples of loaded extracellular vesicles tested in clinical trials include ExoSTING (extracellular vesicles loaded with a STING agonist), exoIL-12 (extracellular vesicles loaded with interleukin-12 (IL-12)). However, there has not been a huge amount of enthusiasm for the use of extracellular vesicles as delivery vehicles, given their high manufacturing costs and variability compared with the more standard approaches of viral vector or LNP delivery. As an alternative therapeutic approach, various therapeutics based on the inherent functional properties of the extracellular vesicles have also been tested in clinical trials, including AGLE-102, bone marrow derived extracellular vesicles for treating burns, and ginger-derived extracellular vesicles for inflammatory bowel disease (NCT04879810). However, again, a big problem is how EV products can be defined for quality control before being given to patients.

Reducing the variability of the product

In T 0827/23, the patent in question (EP 3468568) belonged to Lysatpharma GmbH (a preclinical stage biotech). The patent was directed to extracellular vesicles derived from human platelet lysate for use in treating a range of inflammatory and autoimmune diseases. A key feature of the claimed invention was that the human platelet lysate containing the EVs originated from pooled donor-donated platelets. According to the patent, this pooling was intended to address the inherent variability of such biological products, aiming to provide a therapy with more reliable efficacy. The patent was opposed by the Universität Duisburg-Essen on grounds of, inter alia, lack of inventive step. The Patentee appealed the decision of the Opposition Division to revoke the patent.

The independent claims of the patent did not specify the structural characteristics of the vesicles, but instead defined the vesicles solely in terms of their origin. Claim 1 of the main request on appeal particularly specified a “[p]harmaceutical preparation comprising a fraction that is enriched for human platelet lysate derived extracellular vesicles for use in the prevention and/or treatment of inflammatory driven diseases, immune/autoimmune diseases, transplant rejections, or Graft-versus-Host Disease, wherein the human platelet lysate originates from pooled donor-donated platelets.”

Problem of comparing with the prior art

The Board of Appeal identified two features distinguishing the invention from the document identified as the closest prior art. First, the closest prior art did not use vesicles derived from pooled donor-donated platelets. Second, in the prior art there was no specific combination of human platelet derived extracellular vesicles with the claimed diseases. The Patentee argued that the technical effect of these features was a more reliable efficacy, substantiated by post-published data.

The post-published data included data from an in vivo mouse model study and various in vitro assays for evaluating immunosuppressive effects. The Patentee argued that these data substantiated a noticeable anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive efficacy, a surprising improved effect compared to a standard oral corticosteroid (a known immunosuppressive agent), and that pooling samples from donors provides more reliable efficacy.

The Board of Appeal acknowledged that the post-published data supplied by the Patentee did show the anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive effects of the vesicles. However, the Board of Appeal was quick to point out that no particular effect over the vesicles disclosed in the closest prior art had been substantiated, given that the data provided no comparison. The Board of Appeal did agree that reduced variability due to pooling “appears to be usually recognised based on common general knowledge” but noted that a “direct and necessary correlation between reduced variability and more reliable efficacy has not been substantiated.”

Accordingly, the Board of Appeal formulated the objective technical problem not as the provision of a more effective treatment, but merely as the provision of a vesicle preparation with reduced variability. The Board of Appeal found that, in the absence of any demonstrated superior effect over the prior art, the choice of human platelet derived extracellular vesicles from the various options disclosed in the prior art was an “arbitrary choice, which does not require any inventive skills” (r. 2.5.1).

The Board of Appeal also considered that the pooling of samples to reduce variability was a known and obvious step, noting that the prior art showed that pooling of platelet derived extracellular vesicles had “already been routinely done in the prior art” (r. 5.5.5). The Board of Appeal therefore also considered the second distinguishing feature obvious. The revocation decision was thus upheld.

Analysis

The problem for the Patentee in this case was the lack of comparative data. Whilst the Board of Appeal, in line with G 2/21, was willing to consider the post-published evidence, the Board of Appeal nonetheless remained unconvinced that the evidence demonstrated an unexpected technical effect over the closest prior art. The data might have plausibly demonstrated that the vesicles had the claimed effect of immunosuppression, but it did not show that the vesicles were better than what was already suggested by the prior art.

Ironically, the very problem the invention was trying to solve, namely the inherent variability of extracellular vesicles, may also have hampered the patent strategy for the product. A big problem with obtaining comparative data in biotech is being able to reproduce the prior art in order to make a direct comparison. In the field of cellular and gene therapy, in particular, demonstrating a direct comparison with an existing product may be both prohibitively expensive and technically challenging, especially for cash-strapped biotechs in the preclinical phase. The situation may be exacerbated even further with respect to non-reproducible commercial products now considered prior art and citable for inventive step according to G1/23.

In Europe, it is therefore essential to consider not only the need for data demonstrating that your invention works. It is likely that you will also need data demonstrating that the invention solves a problem in view of the existing technology in the field. This can be easy to forget in situations where the prior art was never clinically developed, and therefore considered irrelevant from a scientific or commercial perspective. However, to achieve robust IP protection in the biotech field, comparative data will often be essential.

At Evolve, we are experts in IP strategy for advanced therapies and biotech inventions. We have extensive experience developing and coordinating IP strategy for cell therapy with regulatory and manufacturing business functions. Do you need advice on how to protect your biotech innovation? We would love to hear from you.

Author: Rose Hughes

Further reading

- Webinar: Unlocking the potential of cell & gene therapies with effective IP strategy

- Falling between the cracks: The challenges of patent strategy for stem cell therapies (T 1259/22)

- Beyond the process: Securing robust IP protection for cell therapies

- Securing market protection for cell therapies: Patents versus regulatory exclusivity

- Too broad, too early? AI platform for cell analysis found to lack technical character and sufficiency (T 0660/22, Cell analysis/NIKON)

- Defining the undefinable: The challenges and opportunities for cell therapy IP

- Non-reproducible commercial products are prior art (G1/23)