The purpose of patents is to protect the market for a product. Within this context, pharmaceuticals is perhaps the industry in which the relationship between patents and commercialisation is most apparent. For pharma, understanding the IP is absolutely core to commercial forecasting and investment decisions. Similarly, within pharma, it is not possible to understand the importance of the IP without also understanding the broader commercial context in which the IP is considered and evaluated.

Forecasting the cliff-edge

In the pharma industry, understanding how IP secures a return of investment is a key financial concept applicable to all types of drugs. The lengthy timelines and multimillion-dollar cost of bringing a drug to market necessitate robust strategies to ensure this return. Research and development costs are exceptionally high, increasing from pre-clinical stages into and through clinical trials, and continuing even after a product launches. This represents a huge investment which needs to be recovered.

The pharmaceutical industry therefore has to think long-term. Companies and investors will not see any returns on investment for many years. It is therefore very important for pharma companies to forecast the return of investment expected many years in the future to justify the present day investment. A key consideration for all pharmaceutical and biopharmaceutical drug products is therefore the date on which market competition is expected to emerge, known as the loss of exclusivity (LoE) date. Once a drug is placed on the market, the innovator company will have until the LoE to recoup its return of investment before the market for the product is eroded.

The LoE date is therefore fundamental for financially forecasting the likelihood of a return on investment for a drug product. This date is not only used to assist investment decisions on internal programs but is also often incorporated into the royalty terms for licensed products. Every investment decision made by pharmaceutical companies, from funding new clinical trials to engaging in collaborations with new companies and pursuing acquisitions, depends heavily on the forecasted LoE date. Consequently, one of the very first questions an IP attorney will be asked about any new drug product or programme is to establish the LoE date. In-house you are asked to predict and justify the LoE date as soon as the project team seeks any significant investment decision. You will then be asked to confirm if there are changes in the predicted LoE at regular intervals, including for any new investment decision and for all the commercially relevant countries, right up until the LoE date is reached.

Calculating the loss of exclusivity date

Patents are the primary mechanism of ensuring market protection for a drug product. The core composition of matter patent for a new medicine will ideally be filed shortly before the product candidate enters the clinic. This action triggers a 20-year clock, ticking inexorably towards patent expiry. In addition to patent protection, LoE may also be determined by regulatory exclusivity, if this runs longer than the composition of matter protection.

Before regulatory exclusivity or the core composition of matter patent for a drug product expires, the market for the innovator’s product is protected (assuming that the composition of matter is robust). Once the product is on the market, which may not be until 10 years after the drug first starts clinical trials, the innovator can begin to recoup their substantial investment. The product’s market share revenue typically increase over its protected lifetime such that the most profitable years for the drug are generally the final years of its exclusivity period. This brings us to the LoE date.

Essential to the understanding LoE is appreciating that a key feature of traditional small molecule drugs is the ease in which they can be easily copied. Generic companies can therefore be poised to bring their copies to market on the very day the market is no longer protected. These generic versions of the drug will launch at a lower price point, they can rapidly capture significant market share, which can then immediately and drastically erode the innovator’s revenue. Often, multiple generic manufacturers will launch at the same time, leading to aggressive price discounting among them, which further accelerates the precipitous drop in revenue for the original drug. For these reasons, one typically observes a steep “patent cliff” in revenue immediately following the LoE for a small molecule drug. The market for small molecules is thus understood based on the principle that these products are easy to define, easy to copy, and easy to manufacture. The primary risk to the market, therefore, comes from generics who will rely on the originator’s data package and launch immediately after the LoE date.

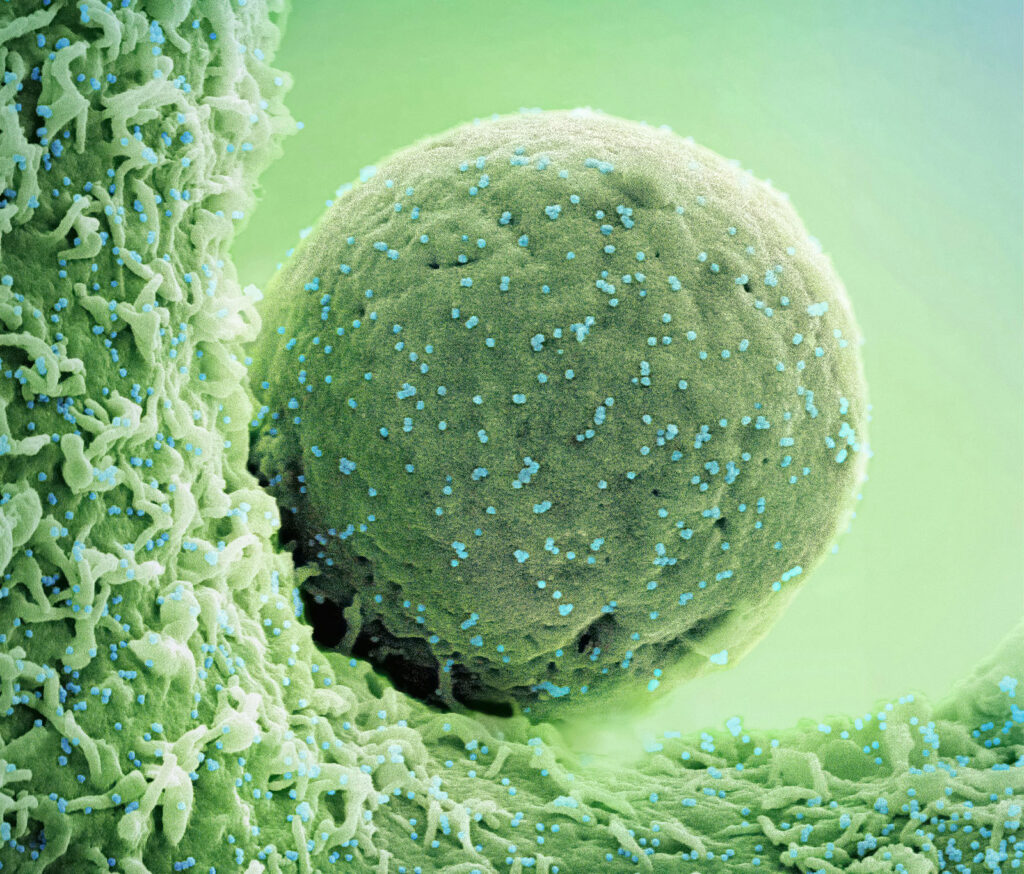

However, the situation is more complex for biologics. Biologics such as monoclonal antibodies are harder to copy and more expensive to manufacture, we generally observe more of a “patent slope” than patent cliff after LoE. The slope is expected to be even less steep for advanced therapies given that they are even harder to copy and more expensive to manufacture. Interestingly, whilst there are a number of currently marketed biologics fast approaching their official LoE date, e.g. as determined by composition of matter expiry, for many of these drugs there are no biosimilars in development poised to launch once “LoE” occurs. This raises the question of whether a more nuanced approach is needed to forecast return of investment and LoE for biologics, which takes account of factors other than IP, such as the competitive landscape and manufacturing challenges associated with a product.

Taking the global view

To add further complexity, LoE is a date that must be determined on a country-by-country basis. There is considerable geographical variation in LoE arising from jurisdictional differences in patent law, provisions for patent term extension and regulatory data protection. For example, in the US, new chemical entities receive five years of regulatory exclusivity, whilst biologics enjoy twelve years. In Europe, by contrast, all new drug products approved by the EMA currently receive ten years of regulatory protection.

The provisions and rules by which a patent may be extended based on market approval for a drug product may also vary widely between jurisdictions. Many countries, including the US, European countries and Japan, offer a maximum term of 5 years of additional patent protection based on a first marketing authorisation for a drug product. However, there are very different rules between the jurisdictions on how this term is calculated. In other countries, no patent term extension may be available. All of this can lead to a situation in which LoE for a drug product may occur in one core market, years before LoE elsewhere. This is currently the situation for Novo Nordisk’s weight loss drug semaglutide, for which LoE in China is next year based on core patent expiry, whilst regulatory protection and patent term extensions protect the semaglutide market in Europe, US and Japan until at least 2031.

Final thoughts

For PatKat, the context of how patents are viewed in the pharma industry is critical to understanding the broader implications of any patent decision in the field. LoE currently provides the foundation for the financial forecasting upon which the entire pharma industry is built. However, despite the importance of the LoE date for all financial forecasting, there are many uncertainties associated with determining this date, particularly when looking more than twenty years into the future. To begin with, the legal and regulatory environment is in a constant state of flux. Patent law itself may change over the twenty-year life of a patent, potentially altering the scope or enforceability of the rights that were originally granted. These developments in patent law may lead, for example, to the invalidation of core composition of matter patents that have been the basis of LoE throughout the life cycle of a drug, see for example the recent AstraZeneca Forxiga case.

The regulatory environment is also subject to change. The European Union, for example, is currently considering significant reforms to its pharmaceutical legislation which may alter the periods of regulatory exclusivity available, and substantially impact the LoE date. Governments may also introduce new drug pricing initiatives, such as those seen recently in the US and those currently in force in Canada, which can profoundly impact the commercial viability of a product irrespective of its patent status. The LoE date may therefore also change over the life cycle of a drug. Whilst these uncertainties do not diminish the critical importance of the LoE date for forecasting, they nonetheless highlight the need for a dynamic and sophisticated IP strategy that can adapt to a changing legal, regulatory and commercial landscape. Additionally, in order to understand the potential impact of any patent decision in the pharma field, it is essential to consider how the IP fits within the commercial framework of the industry.

Further reading

- How to read a biotech patent

- Freedom to operate versus patentability in biotech: What the difference is and why it matters

- IP strategy for AI-assisted drug discovery

- Securing market protection for cell therapies: Patents versus regulatory exclusivity

- Commercial success is a nothing-burger for the EPO in Wegovy patent inventive step analysis (T 1701/22, Obesity treatment with semaglutide)

Originally posted on IPKat.